By: Mandy Flores-Curley

This is the fourth post in a the Refugee Youth Voices series that is uplifting the voices of young people with refugee- and immigrant-backgrounds.

Highlights:

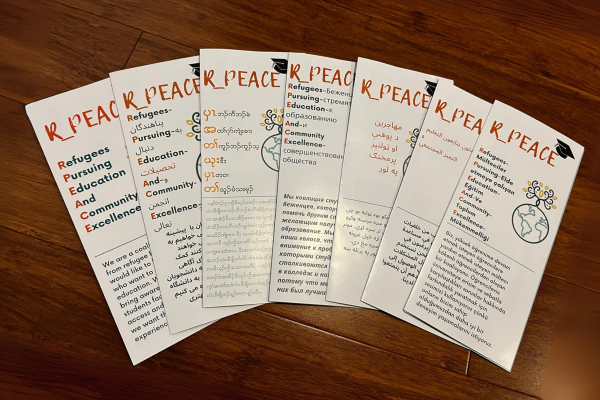

- This post is part of the Refugee Youth Voices blog series, a partnership with the Refugees Pursuing Education And Community Excellence (R_PEACE) coalition, where young people with immigrant backgrounds are sharing their experiences.

- As a former teacher and current graduate student, I am adding to this series by sharing some tips that educators can use to understand the past experiences of their students and language differences.

- In this blog, I share strategies for nurturing learning for students with refugee backgrounds, and addressing trauma with sensitivity and support.

The diversity of the student population in schools today includes children who are refugees, many of whom have experienced trauma that can affect their learning and behavior in profound ways. As educators, it is crucial to develop an understanding for these experiences, adjusting our teaching practices to create a supportive environment.

Here, I want to focus on strategies for helping students who have been traumatized, and like Sue Mar, disturbed by fireworks on the Fourth of July due to their association with past experiences. Here are some approaches tailored for elementary, middle, and high school settings to facilitate a nurturing and effective learning environment for all students.

Elementary School Strategies

- Safe Spaces: Establish a “safe space” in your classroom where students can retreat if they feel overwhelmed. This area should be equipped with calming activities and materials (e.g., books, art supplies). It’s a quiet corner where students can take a moment to regulate their emotions.

- Routine & Predictability: Many refugee children find comfort in predictability. Maintain a consistent daily routine and give plenty of opportunities to learn about transitions and any upcoming events that might be out of the ordinary, including celebrations like the Fourth of July.

- Storytelling & Books: Use stories and books that are sensitive to the experiences of refugees without being triggered. Literature that focuses on themes of hope, resilience, and diverse experiences can be particularly powerful. This approach builds empathy among all students and helps those with trauma feel seen and understood.

Middle School Strategies

- Peer Support: Foster a buddy system pairing refugee students with empathetic peers who can help them navigate school life. This system promotes a sense of belonging and support. Training for these peer buddies on basic understanding of trauma can enhance the effectiveness of this strategy. Note: Be particularly careful that the student is helpful and trustworthy.

- Expressive Arts: Encourage participation in art, music, and drama, which can be therapeutic and offer a form of expression beyond words. For instance, participating in a music class can be a soothing alternative for a student troubled by the noise of fireworks, offering a positive association with sound.

- Inclusive Celebrations: Be mindful of cultural sensitivities when planning school events and celebrations. Offer alternative activities during events that include fireworks or other potentially triggering experiences. Educate the entire school community about the reasons for these adjustments to foster a culture of understanding and respect.

High School Strategies

- Student-led Initiatives: Empower students to take the lead in creating inclusive projects or clubs that address the needs of refugee students. For example, a student group could organize a quiet, welcoming event as an alternative to the traditional Fourth of July celebrations. Note: This has to be done carefully, without giving too much information that the student may not want to share.

- Counseling & Support Services: Ensure that refugee students have access to counseling services that are sensitive to their experiences. School counselors should be trained in trauma-informed approaches to effectively support these students.

- Educational Adaptations: Recognize and accommodate the diverse educational backgrounds of refugee students. This might include differentiated instruction, targeted English language support, and flexibility in assignments and testing to account for varied levels of formal education prior to arrival.

Teaching students who are refugees and have experienced trauma requires a thoughtful and informed approach. By implementing strategies tailored to the unique needs of all students at different educational levels, educators can create an environment that not only supports their academic growth but also their emotional healing and well-being. I believe we should strive to empower these students, helping them feel safe, included, and capable of achieving their full potential in their new community.

If you have any comments or questions about this post, please email Youth-Nex@virginia.edu. Please visit the Youth-Nex Homepage for up to date information about the work happening at the center.

Author Bio: Mandy Flores-Curley, an educator with 14 years of teaching experience, is now a Ph.D. student at the University of Virginia. Her research encompasses English as a Second Language (ESL) and Dual Language Education, student performance, teacher development, and leveraging artificial intelligence to enhance teaching methods. She has a strong commitment to advancing education and she is on a mission to shape the future of learning and teaching.