By: Jessica Stern

Highlights:

- Attachment styles have been shown to shape mental health, but almost no research has examined the experiences of Black teens (this is especially important in light of BIPOC Mental Health Month).

- Our new research reveals that Black teens experience more racism in their neighborhoods, and those experiences of racism are associated with greater attachment avoidance (discomfort with emotional closeness) and with elevated depressive symptoms in the early teen years.

- We also explore other findings, including how attachment avoidance predicted increases in depressive symptoms over time, but only for teens who identified as White; avoidance was not a risk factor for teens who identified as Black.

Think back to your teenage years: Was it a happy time in your life, or did you struggle with feelings of depression? Did you lean on your close friends or family members for support, or did you deal with your feelings by yourself? And did you ever experience racial discrimination in your neighborhood?

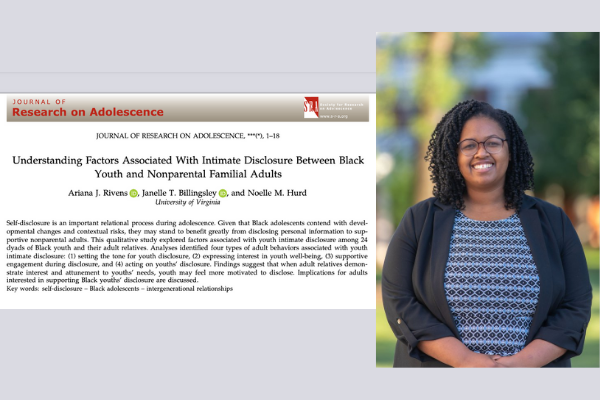

We put these questions to teens themselves to uncover how race, racism, and attachment style — or how we feel and behave in close relationships — shape mental health during adolescence. Our new study, published in a special issue of Attachment and Human Development, explored pathways to mental health for teens with different racial-ethnic identities and experiences of discrimination in their neighborhood.

Teens’ Relationship Styles

We focused on two styles of behavior in close relationships:

- Attachment avoidance – teens’ reluctance to trust others, discomfort with vulnerability, and tendency to deal with emotions alone.

- Attachment anxiety – teens’ worries about their relationships and fears of abandonment.

Previous studies had shown that both attachment avoidance and anxiety foreshadow increased risk for depression— but these studies overwhelmingly focused on White college students. Almost no studies had examined the unique experiences of Black teens, for whom some aspects of avoidance (like being able to suppress vulnerable emotions when necessary) may be understandable —or even protective— in the context of dealing with racism in their daily lives.

We followed 171 teens from Prince George’s County, MD from age 14 to age 18, focusing on teens who identified as Black or as White. Each year, we asked them to report their attachment style, experiences of racism in their neighborhood, and symptoms of depression. We tested a simple but novel question:

Do the well-established links between attachment and depression differ depending on teens’ racial identity and perceptions of neighborhood racism?

Racial Identity & Racism Findings

When we looked at our sample of teens all together, attachment anxiety and avoidance predicted increasing risk for depressive symptoms— replicating most previous studies. But the story was more complex when considering race.

First, Black teens perceived significantly more racism in their neighborhoods than White teens (unsurprisingly), and those experiences of racism were associated with greater attachment avoidance and with elevated depressive symptoms in the early teen years. Second, avoidance predicted increases in depressive symptoms from age 14 to 18 only for teens who identified as White; avoidance was not a risk factor for teens who identified as Black. These effects of racial context were unique to avoidance, and not attachment anxiety.

This suggests that Black teens may cope with racism in their communities by adopting avoidant strategies to manage vulnerable emotions.

Rather than assuming that avoidance is universally “bad” for teens, we can see it instead as an understandable strategy for Black youth dealing with racism that may be protective, at least in the short term. Even so, all Black teens need and deserve close relationships in which they feel safe, secure, and supported in expressing their full range of emotion.

The findings reveal how the pathways linking experiences in close relationships to mental health outcomes can vary by racial context— highlighting the importance of considering diversity in adolescent development. Future research is needed to understand how attachment might interact with racial identity to shape other important outcomes, like coping, resilience, critical consciousness, and racial identity development.

How to Support Black Adolescents

As we consider ways to support positive youth development and mental health, it is critical to understand the unique social and emotional experiences of Black youth. Researchers and practitioners can support Black adolescents by:

- Advocating for anti-racist policy;

- Understanding that moderate levels of avoidance may be a protective strategy for dealing with racism in daily life (that is, not pathologizing teens’ avoidant attachment style); and

- Supporting social relationships in which Black youth can safely express their full selves (for instance, relationships with natural mentors).

If you have any comments or questions about this post, please email Youth-Nex@virginia.edu. Please visit the Youth-Nex Homepage for up to date information about the work happening at the center.

Author Bio: Dr. Jessica Stern is a postdoctoral fellow in the Dept. of Psychology at University of Virginia. Her research focuses on close relationships, child and adolescent development, empathy, and anti-racist scholarship.