By Julia Augenstern

Highlights:

- Mentoring programs are essential resources in many communities and one of the best supported approaches for fostering positive youth development.

- However, despite a long record of empirical support for their positive impact, little is known about how mentoring benefits are rendered or the specific processes by which mentoring relationships work.

- Presented here is recent work to help assess five key mentoring processes with the hope that when used this survey can reveal what makes some mentoring programs more effective than others.

Over the past 30 years, there have been numerous studies that show mentoring can help reduce youth risk of substance use, school failure and delinquency, and can increase their sense of support, connection, and self-efficacy. Not all programs show these benefits, with some even showing null or negative impacts. The question still remains:

What makes some programs beneficial and how do these benefits occur?

This requires looking into the processes that make up mentoring interactions; to understand the “how” of mentoring. Through reviewing theoretical and practical literature on mentoring we identified a set of 5 processes that were commonly mentioned as occurring within mentoring relationship and developed an assessment tool to capture them (See the original research article in the Journal of Community Psychology at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22408).

Five Key Mentoring Processes

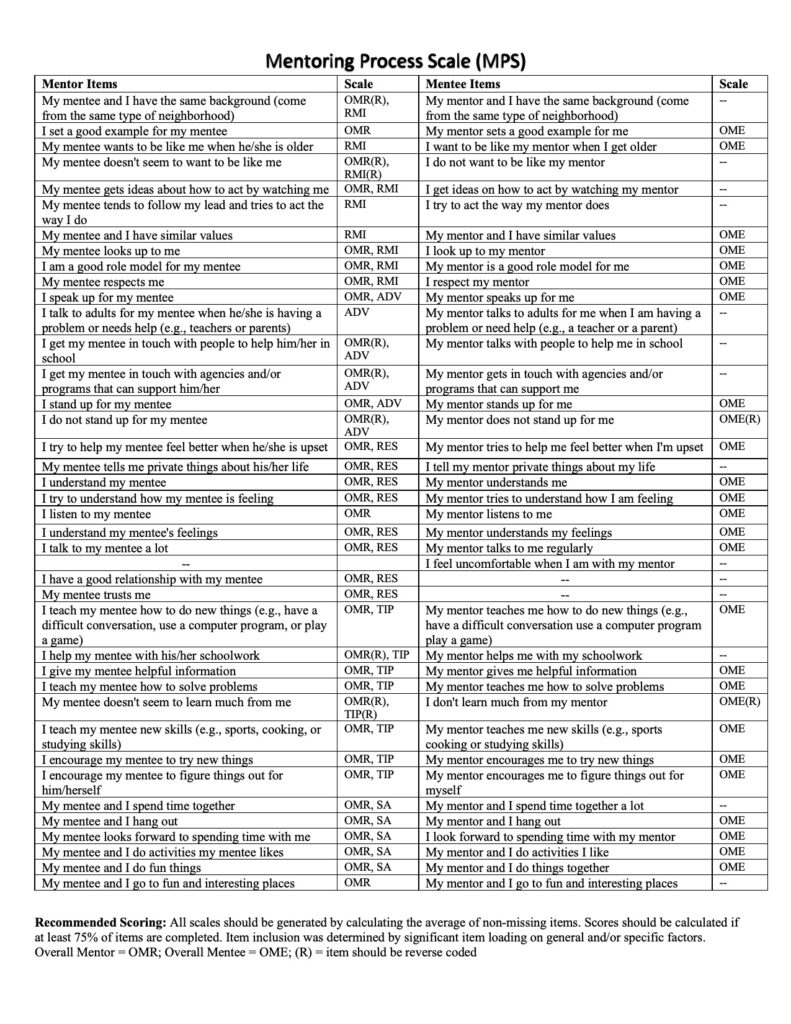

The follow five mentoring processes are measured by the Mentoring Process Scale (MPS):

- Role Modeling – Activities and discussions that provide the mentee opportunity to experience the mentor as a role model or figure of identification, those in which the effect may be to evoke admiration, respect, felt positive similarity and connection, or emulation.

- Advocacy – A process by which the mentor speaks up for or supports the mentee to others, connects the protégé with resources, and/or helps the mentee seek and access skills and opportunities, helping support navigation of social systems.

- Relationship and Emotional Support – Instances where the mentor provides open and genuine positive regard and companionship to the mentee in ways that would be expected to lead the mentee to feel supported and cared for by the mentor. This process is characterized by regular and open communication, with empathy and/or reciprocity prominent.

- Teaching and Information Provision – A process by which the mentor teaches new things to the mentee and/or provides information that might aid the mentee in managing social, educational, legal, family, and peer challenges.

- Shared Activity – The mentor and mentee engage in activities together (e.g., cooking, playing sports, going out to eat, watching tv) or simply spend time together.

Our goal was to capture and understand these processes from both the adult mentor and youth mentee perspectives. Our study validated these five components as distinct and important factors making up the overall scale and showed that these processes relate to other important characteristics of effective mentoring, when rated by adult mentors. For youth, the items formed as a single general positive mentoring activity scale.

We think the scale can help reveal how mentoring works, what differentiates effective and ineffective mentoring, and what might be important training targets and skills for mentors.

This scale also has promise to help address inequities in access to quality mentoring. Presently, too often, the quality of mentoring available is dependent on economic and social resources, with little guidance on critical components of the mentoring relationship. If we can learn what makes mentoring effective, then training can concentrate on those skills and activities. The scale and the practices it measures can be used to help guide initial and ongoing training. It can also be used to highlight if and how mentors might be applying learned skills in their daily work with mentees. By better understanding the mechanisms of positive influences, disparities in mentoring program quality can be better identified and remediated, thus ensuring a greater likelihood for successful mentoring impacts across communities.

Mentoring in COVID-19

Finally, in a world of physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, mentoring programs must adapt to new ways of engaging youth. They must find ways to successfully maintain the mentoring relationship and address new and unique needs of youth and communities. By considering what processes to emphasize and assessing variation in engagement and outcome as different ones are emphasized, we can learn how to ensure effective mentoring in these new circumstances. These five key processes can be helpful in guiding program adaptation to ensure that important components of the mentoring relationship are still maintained, regardless of the modality through which contact is made.

For more information about this research and the MPS, please see:

Tolan, P. H., McDaniel, H. L., Richardson, M., Arkin, N., Augenstern, J., & DuBois, D. L. (2020). Improving understanding of how mentoring works: Measuring multiple intervention processes. Journal of Community Psychology. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22408

or contact Patrick Tolan, Ph.D. at pht6t@virginia.edu

If you have any comments or questions about this post, please email Youth-Nex@virginia.edu. Please visit the Youth-Nex Homepage for up to date information about the work happening at the center.

Author Bio: Julia Augenstern, M.Ed. is a fourth year doctoral student in the Curry School of Education and Human Services Clinical and School Psychology Program. She studies positive youth development and social emotional learning in a Youth Nex affiliate lab and is a recent Curry Innovative, Developmental, Exploratory Awards (IDEAs) grant recipient.